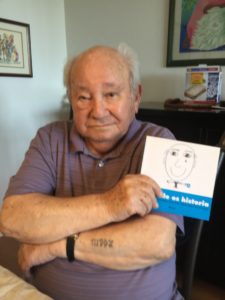

Salomón Schlosser-Co-author, Mi Zeide Es Historia, Born on Yom Kippur, October 7 or 8, 1924, December 24, 1924 (official papers) Solomon passed away December 21, 2020 at the age of 96.

Salomon was born in Lodz, Poland to an Orthodox Jewish family. His earliest memory was reciting Jewish scriptures in a classroom with a Rabbi at 4 years old in a Cheder, a Jewish religious school. As a child he had to work before school–usually selling onions in the market–to help his family make ends meet. The 1930’s in Poland were very calm for Jews. Salomon did not have non-Jewish friends because the Jewish community lived in separate neighborhoods and co-existence was uncommon.

In 1939, after the Nazi invasion of Poland, the Jews of Lodz were forced to move into the Lodz ghetto. Jews were now forced to wear yellow Stars of David both on the front and the back of their clothes, and the Nazis executed any Jews who were caught without it. His father, died in 1940 of hunger. Salomon was in the Lodz ghetto from 1939-1941, until he was transferred to a working camp called Pozen. Salomon remembers the distribution of food rations, getting smaller over time at the hands of the Nazis. What began as a diet of 800 calories was then reduced to 600 calories and eventually down to 200 calories per day.

In 1941, when he was 17 years old, he was at the Pozen camp with 1,000 other Jewish young men ages 16-21. After 2 years in the camp, Salomon was sent back to Lodz together with the only 200 survivors. Upon arrival in Lodz, he was informed by his aunt that his mother and two sisters had been transported by the Nazis to Chelmno. After the war, he found out they had been suffocated and poisoned with carbon monoxide and other toxins from the exhaust of vans that had been stuffed to capacity, and subsequently transported to fresh pits for mass burial.

Salomon’s two brothers had managed to escape to Russia back in 1939. Salomon’s mother had not allowed him to go with his older brothers, as he was too young at the time. His brother Gil, who would be Salomon’s only family member to survive the war, lived into his 80’s in Israel. Salomon’s older brother, Yankl, managed to escape Poland, but was drafted into the Soviet army and killed in action in 1941.

After returning from Pozen, Salomon was sent to jail in the Lodz ghetto. From there, he was sent on to Auschwitz just before Passover in the spring of 1943. The journey to Auschwitz lasted 4 days in subhuman conditions–people were locked into overcrowded cattle cars with no food and no bathrooms for the entirety of the journey. Many passengers died on board. Of every 1,000 people who arrived in Auschwitz, 800 were immediately killed in the gas chambers.

On arrival, Salomon was shaved by a fellow prisoner and then sent to take a shower. In his case, since he was a male of working age, water–not gas—came out of the spout. Whereas the vast majority of prisoners were killed, the Nazis had chosen to keep him alive. He stood in a line and was told to extend his left arm. Within a minute, 2 heated needles were placed on his forearm. Salomon would now be marked for life as prisoner 111907, the number tattooed on his arm to this day. He wore a striped prisoner uniform and a yellow Star of David. Other persecuted groups wore different color stars: Yellow was for Jews, green was for Germans, red for communists and other political prisoners, and pink for homosexuals, who were killed almost immediately. The possessions and precious belongings of the Jews transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau were left in the train carriages and on the ramp as their owners were quickly put through the selection process. Salomon’s initial forced job at Auschwitz was to build a women’s camp, as well as the camp for the Roma, who were also persecuted and murdered by the Nazis.

One day in Auschwitz, a Nazi guard asked a group of prisoners if someone was a Schlosser. Confused, Salomon raised his hand. The Nazi guard asked Salomon, “How many years have you been a schlosser?” He answered that he had been a Schlosser for all 19 years of his life. The Nazi guard was angered by what he perceived as disrespect. The reason for Salomon’s confusion was that he was unaware that Schlosser, his last name, meant locksmith in German. The soldier was looking for a locksmith, not a person named Schlosser. Fortunate to survive the incident, Salomon was put to work by the Nazi guard barefoot, outdoors, on a freezing December night. After a while, the Nazi guard asked Salomon why he had disrespected him. Salomon explained that Schlosser was his family’s last name and that he meant no disrespect. The Nazi soldier responded, “907 you are my shoeshine boy now.” Ironically, this helped him survive. He went on to wash dishes in the soldiers’ quarters, and as a result, he was able to sneak some of their leftovers for himself and other prisoners.

Salomon also managed to communicate with prisoners who worked in the Kanada Commando, who could sometimes get him an extra sweater, or a better pair of shoes. Kanada was a warehouse facility for sorting and transporting all the confiscated belongings that had been left on the train carriages back to Germany. The prisoners who worked there, alluding to Canada, a country that to them represented wealth, gave it the ironic name.

In January 1945, as the allies closed in on Germany, the Nazis closed Auschwitz and Salomon was sent on the infamous “March of Death.” He marched–barefoot initially–for close to a week to Mauthausen in Austria, another Nazi death camp. Most prisoners died in the snow during the march, but a fellow prisoner who gave him an extra pair of shoes saved Salomon’s life. Word got out that the Russians were invading. As the Russians came closer, the Germans evacuated Mauthausen and took the prisoners to Melk concentration camp. They then traveled in a truck from Melk Concentration Camp to Ebensee Concentration Camp where he would eventually be liberated. As news spread of the imminent arrival of American forces, most Nazi soldiers deserted the camp, but the prisoners managed to rebel and kill 52 Nazi soldiers. On May 5, 1945 the 80th Infantry Division of the United States Army finally liberated Salomon from Ebensee.

Recovery after the war was not easy. Many contracted diseases from the horrible conditions, and many others died. Salomon weighed 32 Kilograms, and contracted Typhus. But he held on to the only thought he had for years, “survive, survive survive.” And he did. Salomon lived in refugee camps from 1945 to 1949, mostly in Austria. In 1949, at the age of 25, he finally came to America by ship. He arrived in New York and eventually travelled to Miami, Florida, where he finally felt freedom. The Jewish Federation helped him with $27 per month. He went to school and worked in a kitchen. After that he worked in a hotel. After some time, he returned to New York and sold toiletries at fair trade value.

In 1955, a matchmaker approached Salomon and introduced him to his bride. He moved with her to Mexico City, where he would have his children. He later divorced and continued his work as a businessman with a hardware store named Coyote, and later, a bristles factory.

Salomon married Maña in 1975 and would live together until Maña’s passing in 2018. They moved to Chula Vista in 2003.

Salomon is now 96 years old and lives in Chula Vista. He is the co-author of Mi Zeide Es Historia, the widest circulated Spanish language children’s book on the Holocaust. Over 57,000 copies have been purchased and distributed in Mexico to this day. Salomon still speaks to students in schools about his experiences in the Holocaust. He is more than just a Holocaust Survivor. He survived Typhus at the end of the war, a quadruple bypass surgery, cancer, and a stroke. Through all of these experiences, he maintained the same thought he had so many years ago – “survive, survive, survive.”

He is loving, warm, sweet and my prayer for him is that he keeps us company for many more years!

Who is Solomon today, what would you say to the world, I asked him?

“Stay Alive, that’s it, that’s it. Just stay alive. People don’t talk when they are dead, so stay alive.”